The Question of Educational Justice for Mapuche Youth in Chile

- Hanna Vera

- May 14, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: May 20, 2020

“We need to talk about a model of Mapuche education and a form of passing on the knowledge and wisdom of our culture.” This is a quote from an interview with a rural Mapuche professor that calls on the necessity of the development of culturally appropriate education for Mapuche students in Chile.

The United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, works around the world to promote and protect the rights of children. Most people would agree that children have the right to education, and UNICEF and the United Nations (UN) guarantee that right and more in its Convention on the Rights of the Child document written in 1989. In fact, Article 30 of this document goes one step further and assures that, “children have the right to use their own language, culture, and religion- even if these are not shared by most people in the country where they live.” While this might seem like an obvious right that is already being met in what we think of as modernized nations, it is not a reality for indigenous youth around the world like Mapuche students in Chile.

Who are the Mapuche?

The word Mapuche means “the people of the land.” Originally located in south-central Chile, the Mapuche have existed in present-day Chile since 500 BC and are well known for being one of the only indigenous groups that was able to remain autonomous and not be conquered by the Spanish [1]. When Chile gained its independence from Spain in 1818, the process of Mapuche land loss and culture erasure began as they were displaced, confined to reservations, and systematically killed. This was such a burdensome time period for the Mapuche people that they have petitioned the International Criminal Court against the Chilean government for genocide and crimes against humanity.

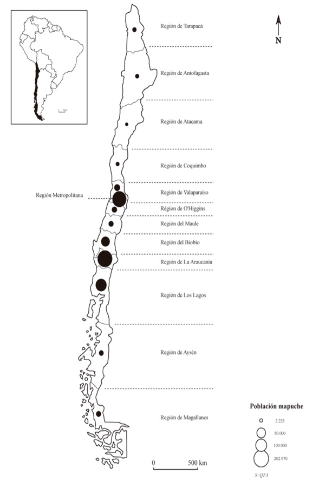

According to a 2017 census, almost 13% of Chileans identify as Mapuche, and their population is strongest in Santiago, Chile’s capital, and their ancestral Araucanía region in the mid-south. Although they are seemingly integrated into modern Chilean society, there are many problems that exist today that are the consequences of their discriminatory treatment in the past and present. The Mapuche community faces police brutality, a prejudiced criminal justice system, and systemic poverty. For Mapuche youths seeking primary and secondary education, they are confronted with an education system that only values mainstream Chilean culture with Spanish as the only language of instruction.

With really no viable option other than to participate in the national Chilean education system, Mapuche students are required to assimilate to mainstream Chilean culture. This forces indigenous students to see their personal culture and language as less valid than what is normally deemed as important academic curriculum. Mapuche students see their ancestors being praised as honorable warriors against the Spanish, yet they are not taught that they personally have value or an important place in modern Chilean society. Even more tragically, fewer and fewer Mapuche children are learning their native language, Mapudungun. Older generations of Mapuche oftentimes intentionally avoid passing down their mother tongue in order to protect their children from discrimination. Because of this and other educational trends, 70% of Mapuche do not speak Mapudungun according to a study by Pereya and Rodrígues de Anca [2].

Mapuche students also face challenges of low academic achievement as there is a significantly large test score gap in Chilean primary schools between indigenous and non-indigenous students according to a 2004 study [3]. Indigenous students tend to live in poorer areas in both urban and rural settings and therefore receive lower quality education than what richer and non-indigenous students receive. Additionally, indigenous students are more likely to enter school late, repeat grades, and drop out early. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Chile’s education system is the second most segregated by class in a study of 65 countries. All of these statistics can be related back to economic and social hardships faced by the Mapuche community.

History of Educational Discontent

The Mapuche people are not the only ones dissatisfied by the current education system. Chile has seen massive student movements against educational inequalities and accessibility in the 2006 Penguin Revolution and the 2011 Chilean Winter protests. The Penguin Revolution was mainly a manifestation of younger students against inequalities of secondary education like all-around unequal funding, and the students initiated nationwide strikes and school takeovers. These students eventually stopped their protests when they agreed to President Bachelet’s plans for a student advisory board, but the discontent was not settled forever. Things boiled over again in 2011 when students led even bigger protests against educational inequalities at the university level. Named with reference to the Arab Spring, the Chilean Winter protests fought for better affordability and accessibility of university education. Both the Penguin Revolution and Chilean Winter protests were student-led educational revolutions that represent the growing dissent over the current education system. Although both protests resulted in small changes, neither fully addressed the systematic inequalities of the education system that still persist today.

How can the Chilean education system be restructured to better serve its indigenous Mapuche student population? Keeping Article 30 from the UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child in mind, it is clear that Chile is violating it as its indigenous students are being deprived of cultural enrichment from the educational system provided. The Chilean state does not value Mapuche culture or language, and the Mapuche lose bits of their mother tongue every day. Without a rigorous language revitalization program, Mapudungun could be unknown to the world sooner than we know it.

Potential for the Future

However, not all hope is lost. Social movements are some of the most important and effective agents of change that we have available to us as a global community. These movements put the power directly in the hands of the people and their communities in order to demand that their needs be met by their leaders. This can be seen in the aforementioned Penguin Revolution and Chilean Winter student movements. The power of social movements can be seen yet again in Chile in the fall of 2019 when massive protests erupted in Santiago. Sparked by a raised metro fare, student activists were the first to jump turnstiles and then take to the streets.

One of the most inspiring photographs taken during the 2019 fall protests in Santiago is of Plaza Italia where over 1 million people gathered to protest ongoing inequalities of their nation. The center of the plaza boasts a massive statue of General Baquedano of the War of the Pacific, and this statue is covered in street art from the social movement as well as covered with the protesters themselves. The sky behind the statue is fiery and clouded with chaotic smoke, and the people on and around the statue are waving banners and the Chilean. Meanwhile, the protester on the very top of the statue waves a Mapuche flag which evokes immense feelings of pride in Chile’s indigeneity as well as solidarity with the Mapuche activism. There are great benefits of bringing youth mobilization and indigenous mobilization into the same fight together as these groups can form a cross-class and cross-group alliances. However, it is important to avoid complete conflation of these two movements as it risks tokenism and infantilization of the Mapuche population.

Infantilization is a process in which groups of people are seen as childlike and in turn relegated to a lower spot in society’s hierarchy similar to that of children. Infantilization can be dangerous and in the case of the Mapuche, it is a direct reflection of their exclusion in Chilean society as a whole just as children are excluded from things in the “adult” sphere. The Mapuche flag waving above all of the rest symbolizes that Mapuche issues and general Chilean issues are no longer entirely separate. Everyone is in this fight together. The young activists of today are an inspiration to older generations and are giving hope to all that the voices of the Chilean people will finally be heard once and for all.

[1] Lydia Nakashima Degarrod, Culture Summary: Mapuche,” New Haven, Conn.: Human Relations Area Files, 2009. https://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu/document?id=sg04-000

[2] Petrona Pereya and Alejandra Rodríguez de Anca, "El Pueblo Mapuche en Neuquén: Ancestralidade, Vigencia y Proyección," in Pueblos Indígenas en la Argentina: Historias, Culturas, Lenguas y Educación, Ed. Gonzalo Blanco (Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Educación y Deportes, 2016): 1-44.

[3] Patrick J. McEwan, "The Indigenous Test Score Gap in Bolivia and Chile," Economic Development & Cultural Change, 53:1 (2004): 157–190.

Comments